Transnational Connections: Bridging Geographic and Disciplinary Divides

Science is not bound by geographic borders, and the scientists featured in this network went to great lengths to pursue their research. Some, like those featured in our data story on totalitarianism, were forced from their homes and moved for socio-political reasons external to science. The women featured below moved for the sake of science, seeking opportunities elsewhere to further their pursuit of knowledge.

Bringing knowledge and experience home

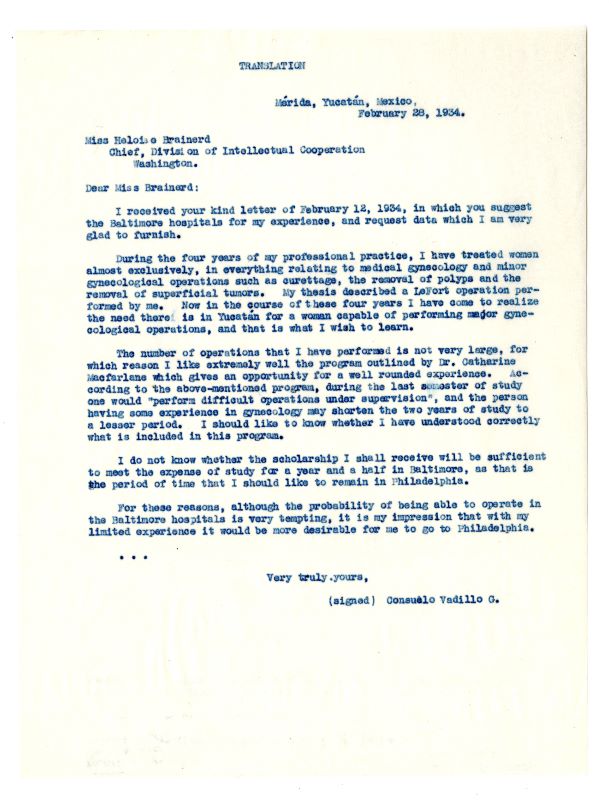

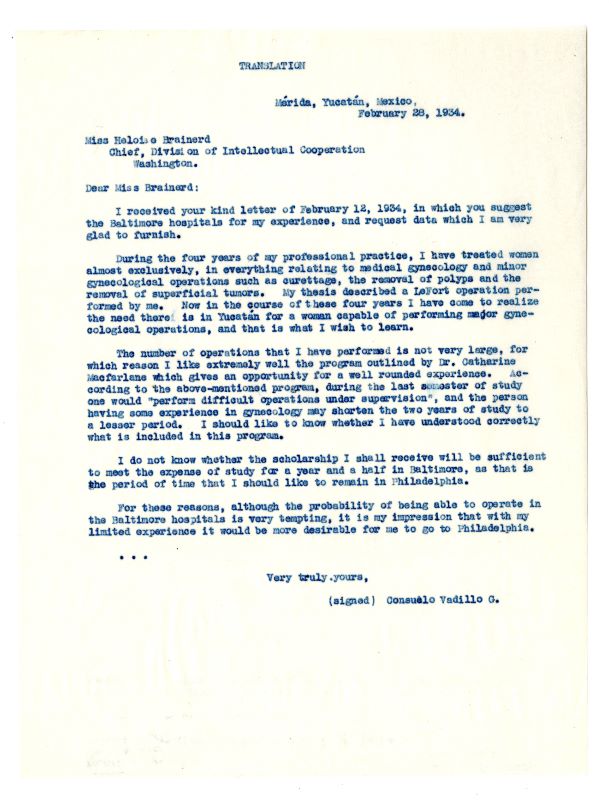

Many women scientists traveled to improve their scientific acumen and bring that gained experience back home. This work was often funded by organizations. For instance, the American Association for University Women not only funded the Naples Table Association, which Florence Sabin had a hand in promoting, but also sponsored scholarships for women from Latin America and Europe to study in the United States. One example is Consuelo Vadillo Gutierrez, a gynecologist from Mérida, Yucatan, Mexico. After being the first woman to receive a degree in 1930 from the National University of the Southeast in Mérida, she came to the United States to study gynecological surgery. To fund her studies, she was awarded a $1500 fellowship from the American Association of University Women in 1934. In her practice in Mexico, she treated “many cases which have never before had treatment because of the existing prejudice against women receiving treatment from male doctors.”1 Vadillo first engaged in a period of observation at Johns Hopkins University and then took up operative gynecology at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. She returned to Mexico and took on private practice, which often meant working with the poorest patients, many who could not pay, and friends of Vadillo remember that she would often treat these individuals for free.2 This story illustrates how women returned to their home country to use their scientific skills and education to improve conditions at home.

Students crossing borders

Not all women scientists represented within the network who studied in the United States return to their home countries. Some end up moving forever, after discovering a new scientific community abroad. This was the case for Eva Soto Figueroa Leake, who also came from Mexico to the United States. Eva Soto Figueroa earned a degree in chemistry, specializing in bacteriology from the Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biologicas, a part of the Institute Politecnico Nacional in Mexico. She worked alongside Eugenia Cardona Lynch at the Sanitario Hospital “Dr. Manuel Gea Gonzalez” in the Department of Pathology in Mexico City. Lynch had a close relationship with both Florence Seibert and Soto and introduced them to each other in 1951. Lynch unexpectedly died later that year, but Seibert continued to do all she could to arrange funding for Soto to study how to treat tuberculosis at the Phipps Institute. After she arrived, Seibert reached out consistently to funding agencies who might offer a fellowship for her. While Soto was guaranteed money from the State Department for a fellowship, she had to wait for nearly four months to finally be paid due to bureaucratic backlog. In 1952 Soto undertook graduate study at the University of Pennsylvania and worked as a research technician under Seibert’s direction. After marrying an American scientist, Keith Leake, Soto, who now went by the name Eva Soto Leake, remained permanently in the United States and took a position at Wake Forest College in North Carolina.

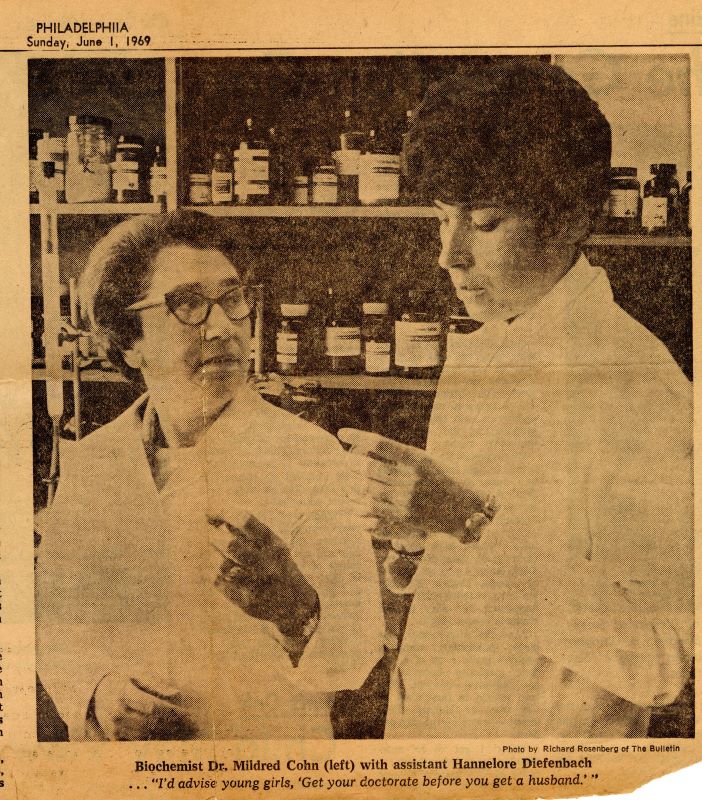

Another example of a woman who studied in the United States and remained for a short time before pursuing other opportunities in another country is Hannelore Diefenbach. Diefenbach worked with Mildred Cohn at the Johnson Foundation Medical School at the University of Pennsylvania from 1960 to 1963 and then again from 1965 to 1972 as a research technician, where she oversaw Cohn’s lab during her trip to Europe. Cohn provided Diefenbach a letter of reference in 1976 after she left the lab to pursue other opportunities. Later in life, she published under Hannelore Diefenbach Jagger in the 1990s from the University of Melbourne, which indicates she made a new home in Australia.

Mutual transnational exchange

Beyond the stories of individuals, though, the network also evidences the role international institutions played in promoting science, for example the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel.

The Weizmann Institute of Science became an academic home for Mildred Cohn. As early as 1952, Cohn collaborated with scientists at the Weizmann Institute, purchasing a supply of a rare isotope of water from them. Over the years, she participated in numerous colloquia and conferences, and even served on their Board of Governors. Not only did Cohn travel consistently to Israel, she also hosted numerous researchers from the Weizmann Institute at her laboratory in Philadelphia. These included Hadassa Degani and Aviva Lapidot, both of whom returned to Israel and became noted chemists and cancer researchers. Cohn’s involvement with the Weizmann Institute was thus a two-way transnational exchange, benefitting scientists in both Israel and the United States. Another woman in science featured in the network was also involved in the Weizmann Institute: Maxine Singer served on the Scientific and Academic Advisory Committee in 1999. Singer appears in both Cohn and McClintock’s direct networks.

By mining the data within the network visualization we begin to see that women were present in science and that they played an instrumental role in promoting scientific research in their home countries and around the world.

Further Reading

Von Oertzen, Christine. Science, Gender, and Internationalism: Women’s Academic Networks, 1917-1955 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).