Gaps and Silences in the Archive

Archives are valuable sources for reconstructing the historical record, but they are not infallible. What gets left behind in a scientist’s papers may only document one aspect of their career or may omit whole periods of their lives. Furthermore, untangling whose contributions count as “scientific” is part of the legacies of exclusion based on gender and race.

In this data story, we will explore some of the ways in which the archive limits our perspective on the accomplishments of women scientists.

Barbara McClintock’s Legacies

How do a scientist’s papers reflect their accomplishments? Barbara McClintock (1902-1992) is most famous for having received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983 for her discovery of “mobile genetic elements,” referred to today as genetic transposition. This finding, which revealed that genes were not fixed on a strand of DNA like a string of pearls but could change position or “jump around,” revolutionized genetics in the latter half of the 20th century, but was largely ignored when McClintock first presented her research in the late 1940s and early 1950s. This has led to a picture of McClintock as a stubborn and dedicated scientist who pursued her own path, regardless of what other scientists might think. Might her papers—or this network—reveal a different story about her?

Though we might hope to find an answer, her papers contain many gaps that make this difficult. Although we know that McClintock worked with several women scientists during her earlier career, many of these connections are not well documented in her papers. In the 1930s, she collaborated with Harriet Creighton in the discovery of chromosomal crossover, another revolutionary discovery. Following this work, she conducted her experiments which famously led to the discovery of genetic transposition in the late 1940s. We know that she worked with Thomas Hunt Morgan at Caltech and therefore knew his wife, famous geneticist Lilian Vaughan Morgan. Yet these names are difficult to find in her papers.

According to a survey conducted in the 1970s by the Genetic Society of America, McClintock failed to preserve her earlier papers. While some papers remain from her earlier career, the bulk of her papers concern her later career following her most important discoveries. This accident of history colors the story we can find in her papers. As a consequence, McClintock’s network tracks her legacy and influence more than her own development. The important players in her network are largely promising students and mentees, such as Virginia Walbot, Vicki Chandler, and Nina Fedoroff, rather than colleagues or mentors. We see McClintock fostering the next generation of researchers who can build off of her accomplishments, right at the moment those accomplishments came to be recognized.

Rose Mooney-Slater’s Social Scientific Networks

Rose Mooney-Slater’s (1902-1981) papers also have gaps and silences. Mooney-Slater was the first woman x-ray crystallographer in the United States and served as the highest ranking woman on the Manhattan Project. Her investigations into the structure of bismuth phosphate were critical in improving the extraction of plutonium from uranium, a necessary step in producing radioactive material in sufficient quantities to fuel the atomic bomb.

Yet there are many gaps in her papers. While moving from Massachusetts to Florida in 1966, her moving van crashed in transit, leading to fire and water damage on several of the surviving documents. Other documents may have been completely lost. And despite her prominent position on the Manhattan Project, the main correspondence from that period is lighthearted personal exchanges, likely due to the heavy secrecy that surrounded the project.

Rose Mooney-Slater’s most significant correspondents tend to be life-long friends who shared both scientific and personal interests. In particular, a group of women scientists from Louisiana, many of whom attended Newcomb College in New Orleans, remained her life-long friends, even when they were all working together in Chicago. Though Mooney-Slater became a nationally renowned scientist, she still maintained tight connections with her home community. She blurred friendship and scientific relationships, fostering deep connections with colleagues and collaborating scientifically with her close friends.

The HeLa Cell

Archives may not only be silent on topics but may reveal an active silencing or suppression of information. An archive may contain a reference to the silenced information, but its presence goes unnoticed and unremarked upon for a long time.

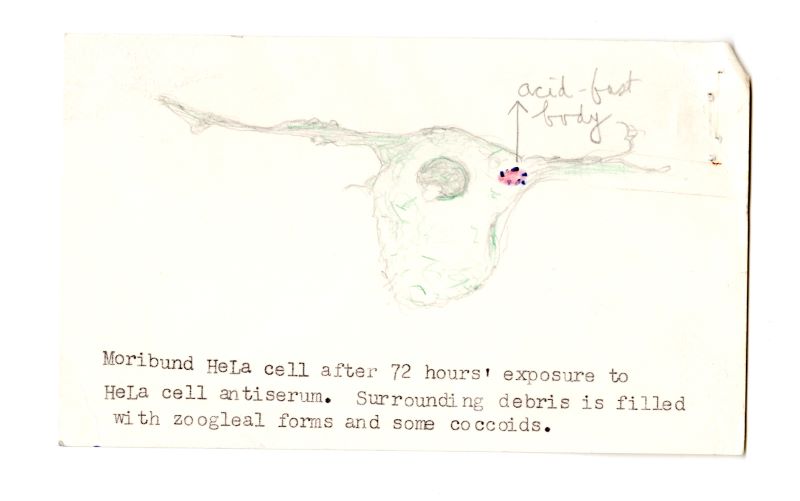

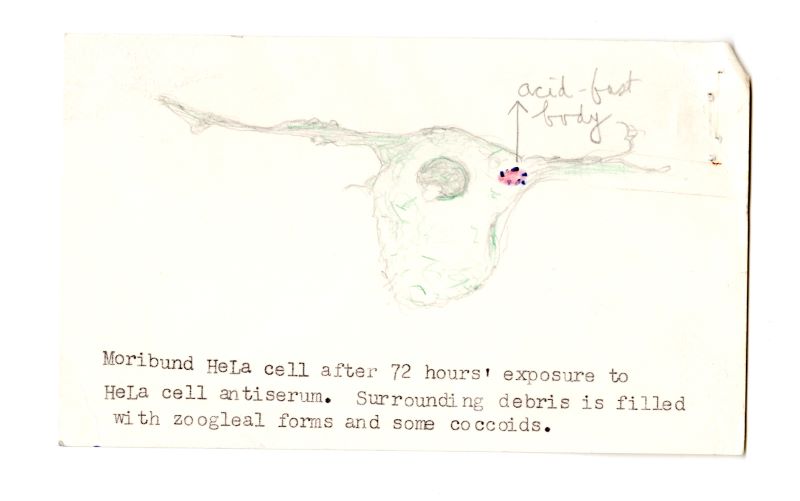

Florence Barbara Seibert (1897-1991) served as a friend and mentor to Irene Corey Diller, a cancer researcher at the Institute for Cancer Research, Philadelphia. Their correspondence spans both personal and professional topics. Professionally, they discussed Diller’s hypothesis that cancer came from a fungus or bacterium. As part of her evidence, Diller hand-drew the results of a HeLa cell. While Diller and Seibert did not discuss the origins of the HeLa cell and perhaps may not have even known where the cell came from, recent journalistic efforts and scholarship have recovered the story of Henrietta Lacks and the contributions she made to science.

Henrietta Lacks was a Black woman who sought treatment at Johns Hopkins University in August 1951 for severe abdominal pain, which turned out to be cancer. After her death in October 1951 researchers collected her cells, without her or her family’s consent or knowledge, and used them to create the first immortalized human cell line, named “HeLa” after the first two letters of Lacks’s first and last names. Since these cells rapidly reproduce in a laboratory setting, they have become incredibly instrumental in many scientific breakthroughs, including testing human reactions to vaccines and the study of diseases like AIDS, leukemia, and cancer. This is how Irene Diller ended up using HeLa cells and how a drawing of the cells entered the archive and this visualization.

Henrietta Lacks’s contributions to science are vast. Many of the scientists featured in this visualization after 1951 relied on HeLa cells to do their research, yet Lacks is not acknowledged by any of the scientists who used her cells. So many scientific discoveries rely on the HeLa cell that this visualization would look very different had the HeLa cell line not been immortalized in 1951. In many ways this story calls attention to the limitations of human efforts at record keeping and categorizing: first, Henrietta Lacks’s name and contribution of the HeLa cell remained unknown to many scientists for decades; second, the HeLa cell in the archive, while present, remains underdescribed in finding aids and catalogs; and finally, on its own this network visualization can’t account for the immense contributions made by Henrietta Lacks. By recognizing these silences and gaps, we can begin to present a full picture of the many different ways women contributed to scientific research.

Further Reading

Comfort, Nathaniel C. The Tangled Field: Barbara McClintock’s Search for the Patterns of Genetic Control. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Glass, Bentley. A Guide to the Genetics Collections of the American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society Library, 1988.

Keller, Evelyn Fox. A Feeling for the Organism: The Life and Work of Barbara McClintock. New York: W.H. Freeman & Co, 1983.

Skloot, Rebekka. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Crown Publishing, 2010.