Florence Sabin’s Networks

Perhaps it is easy to imagine the pioneer as a brave, independent figure who faced the world on their own. This couldn’t be further from the truth, though, if we look at the network connections of Florence Sabin, often considered one of the “first” women of modern science.

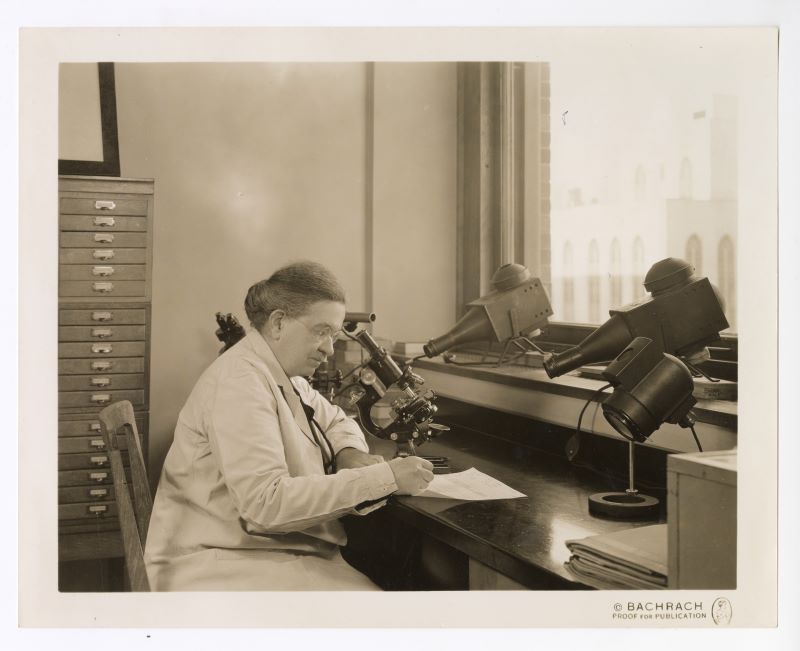

Introduction to Florence Sabin

Florence Rena Sabin (1871-1953) is often referred to as a pioneer of science, although she never referred to herself that way. Among her accomplishments include the following pioneering achievements:

- She was one of the first female graduates of Johns Hopkins Medical School,

- Her book An Atlas of the Medulla and Midbrain (1901) became a well-known anatomy text for decades,

- She was the first woman to become a full professor at a medical college with her promotion at Johns Hopkins in 1917,

- She was the first woman voted into the National Academy of Sciences in 1925.

As the “first” and sometimes only woman in many settings, Sabin was indeed a pioneer in science. But Sabin did not do this work on her own, nor did she keep her connections and successes to herself.

Sabin’s life offers an example of how a successful woman in science sustained and contributed to a wider network of women scientists, some who did not become “firsts” or are even remembered today. By using the data gleaned from this project, we can see the network of women who worked with Sabin, supported her, and who she supported in turn. Sometimes this support was individualized—letters of encouragement and reference sent to and from Sabin to others. At other times this support was formalized—through clubs and fellowship opportunities intending to increase women’s participation in the sciences.

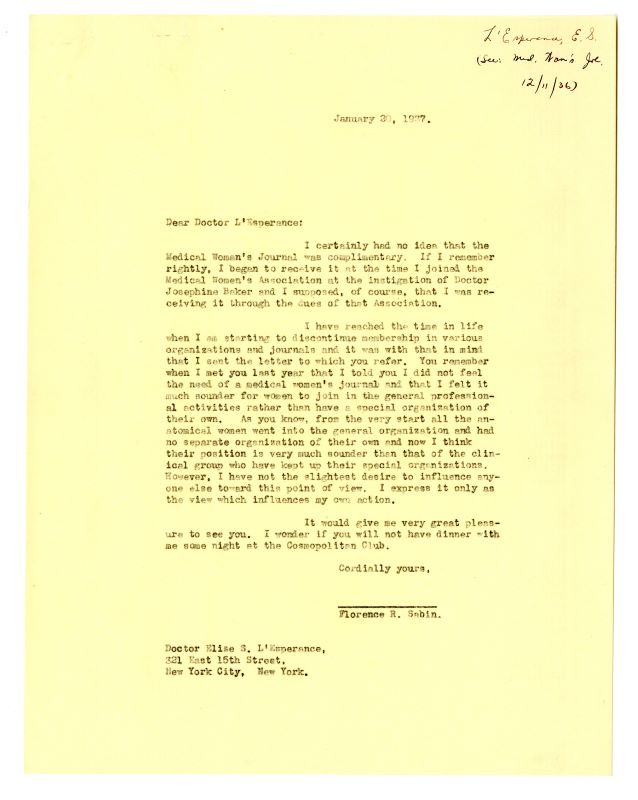

Sabin herself sometimes vacillated between the belief that women’s organizations built by women and for women were vital for encouraging women’s participation in science, and the belief that it was more effective to fight for inclusion within the existing structure and not trying to work outside of the male-dominated societies and organizations.

In a letter to Elise L’Esperance, Sabin notes she does not “feel the need of a medical women’s journal and that I felt it much sounder for women to join in the general organization and had no separate organization of their own. As you know, from the very start all the anatomical women went into the general organization and had no separate organization of their own and now I think their position is very much sounder than that of the clinical group who have kept up their special organization.”

Throughout her life Sabin would try both approaches and she became involved with and supported women’s organizations and opportunities for women in science. One illustrative example that demonstrates the connections of women in science is the Naples Table Association, funded by the American Association of University Women (AAUW).

Naples Table Association

Florence Sabin was involved with the Naples Table Association throughout her career. This association held a research station at the Naples Zoological Station in Naples, Italy that it made available to excellent women scientists. It also administered the Ellen Richards Memorial Prize, a prize for women scientists of the highest caliber. Early on in her career, Florence Sabin was the recipient of this prize. Later, she was a key organizing force in the association, selecting candidates for research fellowships and prizes.

The Naples Zoological Station at the Naples Marine Biological Laboratory opened in 1875 under the leadership of Anton Dohrn, who envisioned a research space for international scientific research into marine life. As part of funding the station, Dohrn introduced a subscription-type model where universities and research institutes would pay a fee to hold a “table” or space to send researchers. Heidelberg University sent Ida Hyde, the first woman to obtain a PhD at Heidelberg, to occupy their seat at the Naples Table in 1896.

Hyde’s struggle at Heidelberg University is part of the story of how women came to occupy the Naples Table. When Hyde first applied to Heidelberg University, physiology professor Wilhelm Kühne jokingly agreed to examine Hyde at the completion of her studies, if she should ever make it that far. When pressured to follow through on his claim, however, Kühne did not allow Hyde to attend his lectures or work in the laboratory. Hyde received research notes from male research assistants, and this assisted in her passing her doctoral examination in 1896. Kühne then permitted Hyde to work in the laboratory and would go on to recommend her for Heidelberg University’s seat at the Naples Table Association.

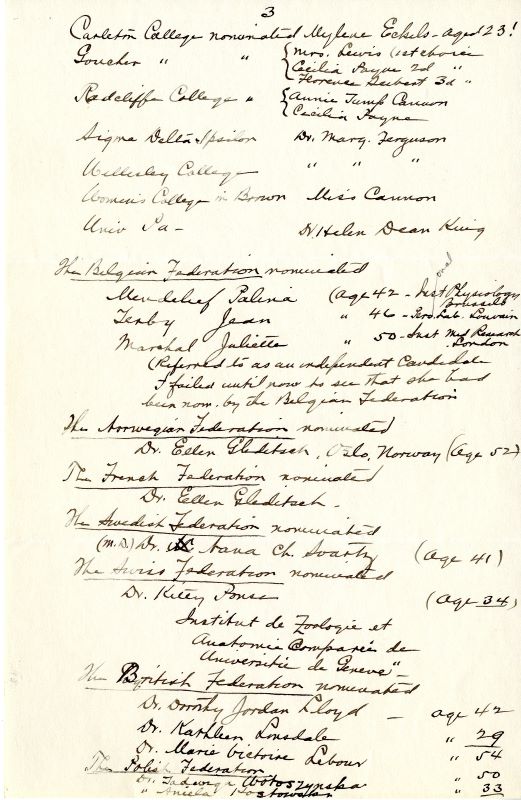

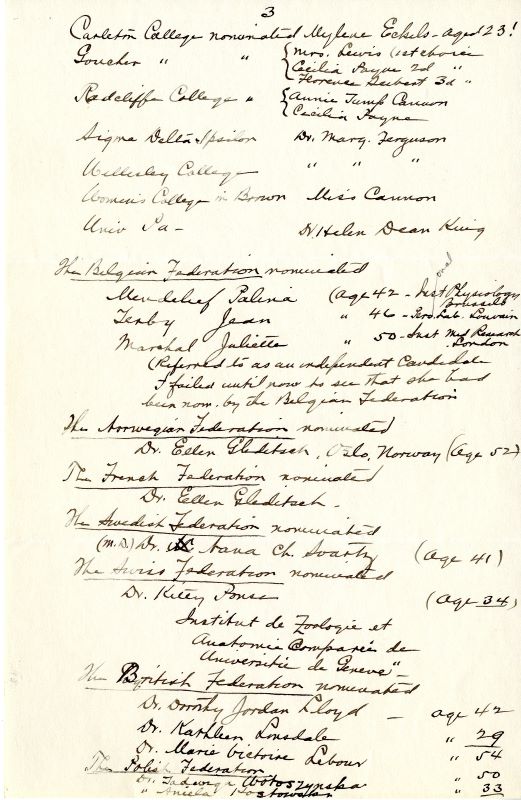

Overwhelmed with the excellent facilities and space to conduct her own research, Hyde presented the Naples Table’s subscription model to the women at the Association for Collegiate Alumane (ACA) that would later become the AAUW in 1921. The women formed The Naples Table Association for Promoting Laboratory Research by Women and sought out subscribers to cover the costs of holding a research station in Naples. Subscribers included Bryn Mawr, MIT, Radcliffe, Smith, Vassar, Wellesley and the ACA. As the number of subscribers exceeded the costs needed to cover the price for the research station in Naples, the excess money was saved and used to fund a prize of $1000 to $2000 for excellent research by women scientists. Named in honor of the first woman professor at MIT, the Ellen Richards Research Prize sought to highlight excellent accomplishments by women scientists and was awarded only to scientists of the highest caliber, including Marie Curie and Lise Meitner. Florence Sabin received the prize in 1903 and was on the prize selection committee from 1915 to 1932.

Use the interactive visualization to explore applicants, recipients, and reviewers of the Ellen Swallow Richards Prize.

The Naples Table sponsored nearly 40 women to attend the zoological station until 1932. The Ellen Richards Research Prize awarded $17,000 to women scientists and this association by women and for women was instrumental in providing women scientists the funds and space to conduct their own research. Florence Sabin was a key figure in the administration of the association. She read applications for researchers at the Naples Table and also was part of the selection committee for the Ellen Richards Research Prize.

In 1932, the Naples Table Association was dissolved. The organizers of the table concluded that “the objects for which this Association has worked for thirty-five years have now been achieved, since women are given opportunities to engage in scientific research on an equality with men.” This proclamation reflects Florence Sabin’s ambivalence about associations specifically for women and her belief it was better for women to engage in the same societies as men. However, the struggles encountered by other women documented in this project may cast doubt on the conclusions of the organizers.

The graph below shows the number of nominations by field for the 1928 Ellen Richards Research Prize. Of note are the high number of nominations in fields that were generally more open to women (botany, pathology, and psychology), as well as the comparatively high number of nominations in “prestige” fields such as physics.

Further Reading:

Ida Hyde, “Before Women Were Human Beings” located at https://biology.ku.edu/Ida-Hyde-Article.

Jan Butin Sloan, “The Founding of the Naples Table Association for Promoting Scientific Research by Women, 1897” Signs (Autumn 1978): 208-216.

Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn Napoli, “Our History” https://www.szn.it/index.php/en/who-we-are/our-history.