Scientists Fleeing Totalitarianism

The turbulent conditions in 20th century Europe displaced a number of renowned scientists. As totalitarian governments rose in Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union, scientists lost their positions and fled their homes. Jewish researchers were targeted by antisemitic policies in Germany and Italy. Political dissidents were also forced to flee. For women scientists who often had already faced great barriers establishing themselves in their home countries, the journey to a safer life was not easy or straightforward. In this data story, we track some of the tales of migration uncovered in creating this network.

Finding Jobs for Displaced Scholars

With the transfer of power to Adolf Hitler’s government in Germany in 1933, many Jewish scientists fled Germany seeking work elsewhere. With the passage of the Racial Laws in 1938, Italian Jews also lost their jobs. In addition, political dissidents were targeted, and working conditions became more difficult for women in general. Numerous letters seeking jobs for these scientists have ended up in the APS archives. Due to restrictive quotas on immigration, scientists often needed an offer of employment before they could flee for another country. But such offers were difficult to come by and could require intensive networking efforts, creating unexpected connections.

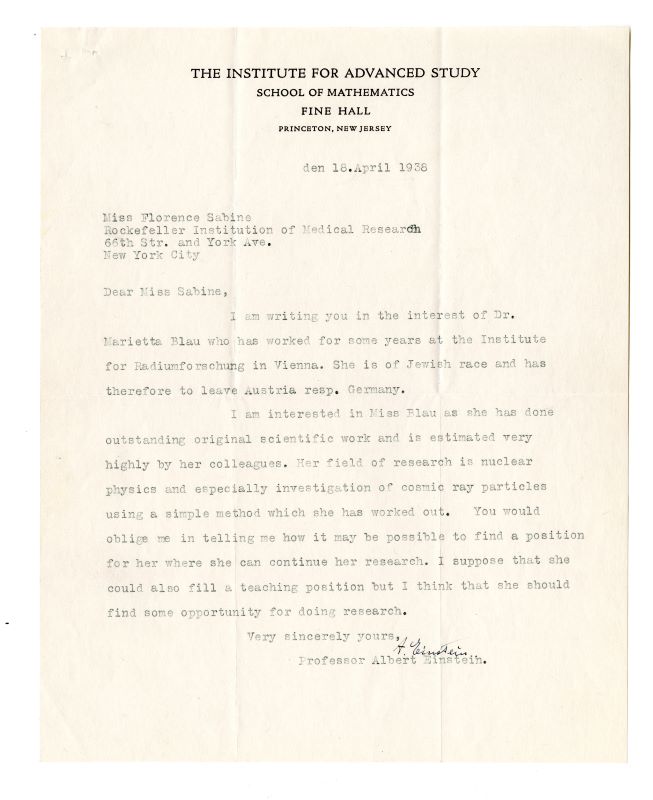

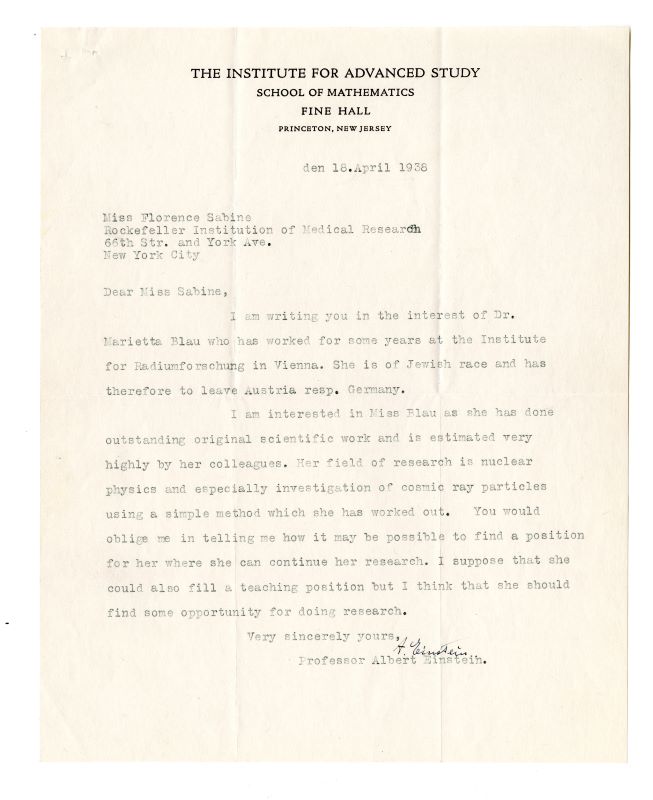

For example, Florence Sabin’s only correspondence with Albert Einstein within the archive concerns two scientists fleeing fascist Germany. Sabin organized a memorial fund in honor of Emmy Noether, a brilliant mathematician who received a position at Bryn Mawr College after fleeing Germany in 1933. Noether unfortunately died shortly after arriving, and Sabin sought to raise funds in her honor to promote future women mathematicians. Einstein provided a letter of appreciation, later published in the New York Times, for use in Sabin’s efforts.

Einstein also reached out to Sabin about finding a job for Marietta Blau, an Austrian physicist seeking to leave her country. It seems Sabin was unable to assist, as was also the case for letters she received about physicists Lise Meitner and Hertha Sponer.

The interactive map below allows you to chart the journeys that some of these scientists took in search of safety and better working conditions.

Ambiguous Stories

It is easy to view these scholars who migrated in a narrative of American exceptionalism, in which they left horrific conditions for a better life in the United States. This is not necessarily true for all, and some scientists held mixed feelings about their new home country. For example, Emmy Noether had spent a year as a visiting researcher in Moscow while she was still working in Göttingen. Noether had sympathies for socialist politics and intended to return to Moscow upon losing her position in Germany. However, the position in Moscow never materialized and she went to the United States instead, taking a position at Bryn Mawr. During this time, she also frequently lectured at Princeton. Noether missed the devoted students she had in Germany and was put off by the chauvinistic culture she encountered at Princeton. She died unexpectedly in 1936, but Florence Sabin used her legacy as an example of the great potential of American universities. While trying to find a position for Lise Meitner, for instance, she hoped a women’s college might hire her in order to “win the same esteem that Bryn Mawr College did when it offered a position to the distinguished mathematician, Emmy Noether.”

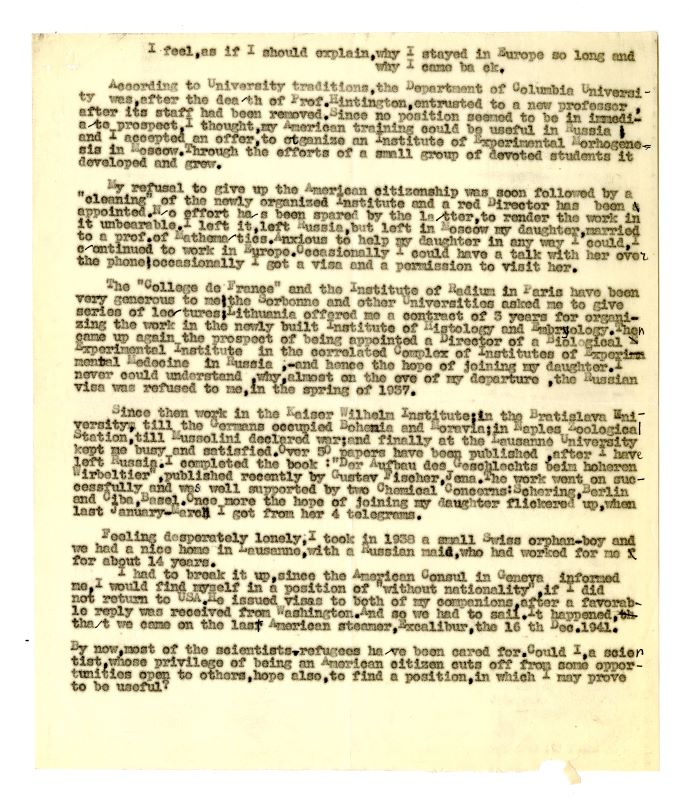

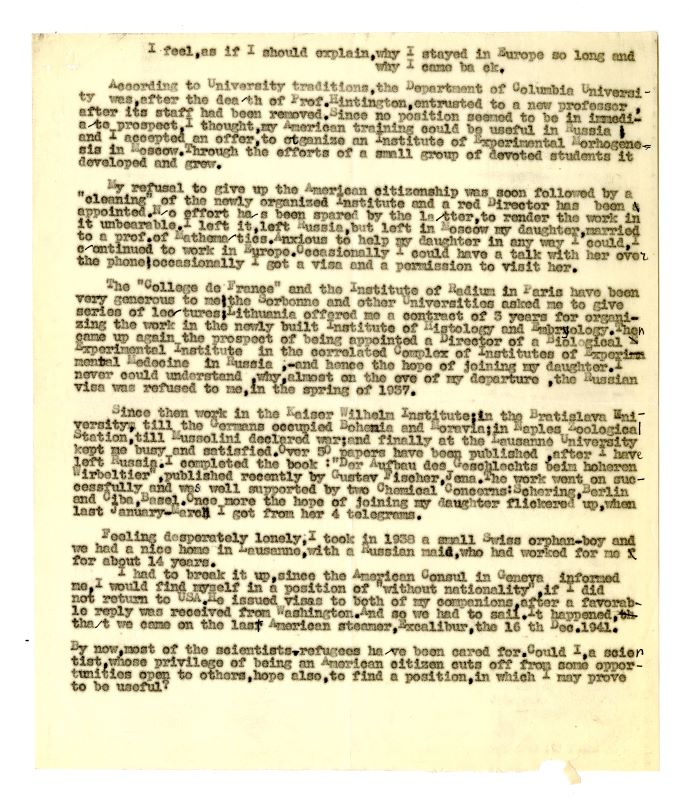

A particularly interesting and ambiguous case is that of Vera Danchakoff. Danchakoff had left her native Russia well before the Soviet revolution and worked in the United States throughout the 1920s. In New York City, she was a foreign correspondent for the Russian press and advocated for improved conditions for scientists in the Soviet Union. In 1927, she traveled throughout the Soviet Union, helping improve scientific facilities. In letters held at the APS, she provides her American colleagues with updates on her journey. Since she had become an American citizen, she was unable to stay long-term in the Soviet Union. By 1929, she returned to New York.

But around 1934, her department at Columbia dissolved after the death of its chair. With no immediate career prospects in the United States, she returned to Europe, taking a position in Lithuania. She had a three-year appointment and visited her daughter in Moscow frequently during this period. Very few sources document Danchakoff’s life after her time in Lithuania. However, in a letter contained in the Warren H. Lewis papers, Danchakoff relates her complicated journey out of Europe. Around 1937, she stopped receiving visas to visit her daughter in Moscow. With the end of her position in Lithuania, she took another position in Bratislava. She remained there until German forces invaded in 1939, fleeing to Naples. In 1940, Italy joined the war, forcing Danchakoff to flee to Switzerland. She adopted a Swiss orphan and may have planned to stay there long term, but was forced to return to the United States. As she was a US citizen, she was informed in 1941 that her citizenship would be forfeit if she did not return immediately to the United States. No sources available to the project team were able to document her life after returning to the United States.

Danchakoff’s story shows the difficulty many of these scientists faced in finding a home. While the United States afforded good positions to many, some did not receive favorable positions. Many missed their families and home countries and made great efforts to return.

Further Reading

Ash, Mitchell G. and Alfons Söllner, eds. Forced Migration and Scientific Change: Emigré German-speaking Scientists and Scholars after 1933. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Duggan, Stephen and Betty Drury. The Rescue of Science and Learning: The Story of the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars. New York: Macmillan Co., 1948.

Fleck, Christian. Etablierung in der Fremde: Vertriebene Wissenschaftler in den USA nach 1933. Frankfurt am Main/New York: Campus Verlag, 2015.

Graham, Loren R. Science in Russia and the Soviet Union: A Short History. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

“Rediscovering the Refugee Scholars of the Nazi Era.” Northeastern University, n.d. https://www.northeastern.edu/refugeescholars/home.

Shen, Qinna. “A Refugee Scholar from Nazi Germany: Emmy Noether and Bryn Mawr College.” The Mathematical Intelligencer 41, no. 3 (2019): 52-65.