About this Project

Ben Franklin: Diplomat, Inventor… Mailman?

Benjamin Franklin was an astonishingly prolific Founding Father. He looms large in popular memory as an accomplished writer, newspaper printer-publisher, statesman, scientist, and socialite. But before he invented the lightning rod, charted the Gulf Stream, or helped to draft the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Franklin was Postmaster of Philadelphia beginning in 1737. He remained in leading postal administration roles until he retired as the nation’s Postmaster General in 1776, at the age of 70. Curiously, despite his involvement of nearly 40 years, this aspect of Franklin’s civic engagement has been the subject of little study in comparison with his other achievements.

"Franklin's Philadelphia Post Office Ledgers: A Glimpse Into Colonial Correspondence Networks" is a multi-year digital initiative by the American Philosophical Society's Center for Digital Scholarship intended to remedy this gap in the scholarship by bringing Franklin’s post office documentation to the foreground. This project is a part of the Society's Open Data Initiative.

Significance

Historians gather and analyze evidence to develop informed conclusions about the past. Throughout this process, they seek to answer fundamental questions like: What? How? Why? When? Where? Who? Arguably the most vital question that a historian must answer, however, is: So What?

- Tidiness, Virtue, and Success

-

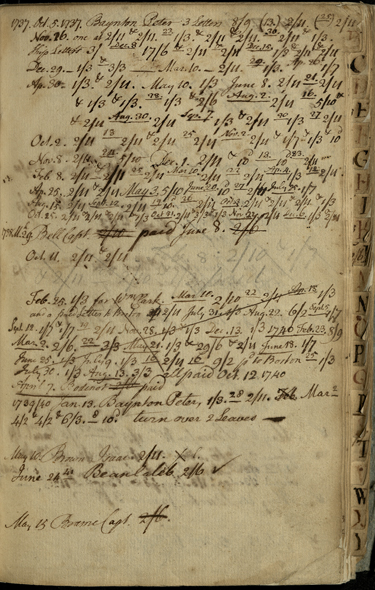

Franklin himself did not write extensively about his roles in the postal service in his memoirs. Rather, the brief anecdotal references throughout The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin serve to promote the merits of a virtuous, well-ordered life. In them, Franklin claims he came into his first Postmaster position in Philadelphia in 1737 because of the administrative ineptitude of his predecessor, Andrew Bradford. The moral of the story? “I mention it as a lesson to those young men who may be employ'd in managing affairs for others, that they should always render accounts, and make remittances, with great clearness and punctuality. The character of observing such a conduct is the most powerful of all recommendations to new employments and increase of business.” This systematic organization and attention to detail, Franklin adds, were key to his subsequent success as Postal Comptroller and Deputy Postmaster General - a claim that is borne out in the evidence of his account books.

- Franklin, Founding Father of the USPS

-

Click here to see the evolution of Franklin's system. Benjamin Franklin’s efforts were paramount in transforming the colonial postal service into a system that is recognizable in the present. Following a 1753 inspection tour of Post-Offices in the northern colonies in his capacity as post office comptroller, Benjamin Franklin was appointed deputy postmaster general along with William Hunter. Inspired to enact reforms in the postal system, Franklin drafted a number of bookkeeping and organizational guidelines to be followed by local postmasters. He also organized several instruction sheets for postmasters to emulate to keep their accounts. The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (volume 5) estimates the composition and printing of these instruction sheets occurred in late 1753. It is certain that Franklin drew on his own experience as local postmaster in devising a postal process that would be efficient and precise, and minimize errors. For example, the way Franklin filled out the Post-Office Ledger held in the APS collections evolved slightly from 1748 to 1752, resulting in later entries that more closely resemble the model entries in the 1753 instructional sheets. Less documentation exists regarding how the post office functioned prior to 1753. But based on the types of reforms attempted by Franklin, there is reason to believe that practice would have varied regionally.

In Franklin and Hunter’s 1753 reforms he provides a model accounting book that clearly separates letters into categories by number of pages: single, double, treble, pacquet. It is curious, however, that he didn’t keep this account in his own book for Philadelphia. This makes it impossible to tell how many items transported by the postal system were newspapers or broadsides. Given this lack of information, it would be difficult to extrapolate a relationship between print and manuscript items in Franklin’s local post office, but it is significant that he thought to suggest it as a model for other postmasters to emulate.

Other reforms in the postal accounting system suggested by Franklin and Hunter set out policies to address issues of security and standardization. For example, item seven established that a table of postage rates would need to be hung “up in your Office in a Frame, to be preserv’d for your Government, and the Satisfaction of all Persons paying such Postage.” Items eight and ten set out procedures for prevention of private, non-postal collection and distribution of mail and for security (“You are not to trust any Person whatsoever for the Postage of Letters or Pacquets, but at your own Risque.”) Item nine suggested a system for disseminating letters not picked up at the post office.

- Reassessing Evidence through a Digital Lens

- How can we use new technologies to revisit previously overlooked documents?

A digital reimagining of an iconic portrait. Much of the primary source documentation relating to Franklin’s time as Postmaster of Philadelphia (1737-1753) and Postmaster General of North America (1753-1774) are held in the collections of The American Philosophical Society. Some of the items—including a 1764 “Table of Distances and Rates of Postage in North America”—have previously been reprinted in publications such as The Papers of Benjamin Franklin. However, until now his postal account books have only been described in summary because they were not deemed significant enough to reprint in full or part. In fact, when the editors of the Papers of Benjamin Franklin composed volume 2 of the series in 1961, they decided that “The thousands of entries are individually of no historical importance and are not reproduced here; rather, each book is described in sufficient detail to make clear its nature and to suggest the light it may shed on Franklin’s operations as postmaster at Philadelphia.”Advances in computing technology in the decades since the 1960s have dramatically altered the scholarly information landscape in a way that no one, including the esteemed editors of the Papers of Benjamin Franklin, could have fully anticipated. Inventions that earlier scholars would have considered fantastical—the word processor, the personal computer, the internet, the practice of cloud computing—have arguably made scholarship more accessible, collaborative, and transdisciplinary than ever before. Methods and capacities of computational analysis have proliferated alongside these innovations, with their implementation in the humanities following close behind. Today it is possible for researchers to interact with materials, reveal new insights, and share their findings in unprecedented ways that make it clear that individual ledger entries can be “of historical importance.”

A number of scholarly undertakings have explored related topics in recent years. For instance, Wheaton College’s Kathryn Tomasek and Syd Bauman devised Encoding Historical Financial Records, which uses Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) methods to annotate financial ledgers. Stanford’s projects within the Mapping the Republic of Letters initiative unveil the vast social and intellectual networks of the Enlightenment through analysis of contemporary correspondence. And most recently, the collaborative Prize Papers Project has the potential to reveal even more global interconnections as they digitize and study a cache of never-delivered letters and ships’ cargo dating from the 17th to the 19th centuries.

Similarly, the postal account books in the APS collection reveal a wealth of information about trade patterns, information exchange, and accounting practices of the 18th century. Multi-level analysis of the information can help scholars understand the flow of publications, currency, and ideas in colonial America.