From Rags to Riches: Paper in 18th Century Phildelphia

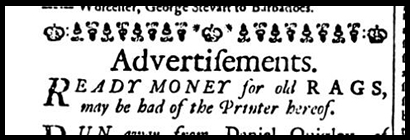

The materials and goods moving in and out of the shop were incredibly varied. It may strike the contemporary eye as strange that rags were among the most frequent commodities that changed hands in Franklin’s shop. However, in the 18th century, rags were a crucial component in papermaking and therefore essential to the Franklins’ business. Rags were so important to the Franklins that they began to advertise in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1734 that they had “ready money” for good quality rags. Why did Franklin make this plea to the readers of his newspaper? The answer can be found in the account books.

Franklin told an acquaintance that he helped establish eighteen paper mills in North America. It seems a peculiar thing to boast about. In the twenty-first century, paper is a cheap and readily accessible good. However, in the eighteenth century it was a limited resource, especially in North America where, until 1690, all paper had to be imported from Britain and Europe. Paper was the essential product for Franklin’s business. Most of his ventures, printing the news, books, advertisements as well as wrapping shop purchases, required paper. Additionally, a large portion of the purchases in the shop by customers were for paper in a vast variety of types.

Use the interactive visualization below to explore the various types of paper found in Franklin's shop.

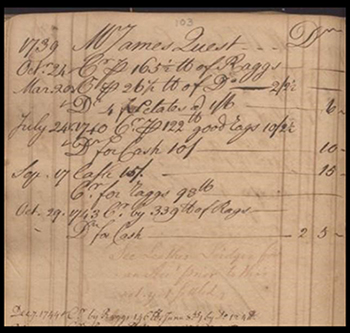

Although the accounts do not reveal the sources for all of the scrap fabric, the Franklins obtained and sold over 180,000 pounds of rags in the 1730s and 1740s. The rags were bought almost entirely by papermakers who had established or were establishing paper mills in Philadelphia and elsewhere. Thomas Wilcox, a papermaker who made pasteboard and experimented in paper money techniques, bought the most fabric scraps from the Franklin, purchasing between 5,000 and 7,500 pounds of rags per year. Use the DataStory below to learn more.

After the rags were bought in the shop, the papermakers needed to move them to their mills. As evidenced by the map below, paper mills were far from city centers as papermaking required clean water. Consequently, the closest paper mill to Franklin’s shop was over six miles away on Wissahickon Creek. Wilcox’s mill was an even greater distance at over 18 miles as the crow flies. Franklin even sent rags to William Parks in Virginia. On average each load of rags moved to a paper mill was 1,300 pounds, about the weight of one and a half grand pianos.

Once at the mills, the papermakers made a range of different types of paper from fine letter quality to brown paper meant to wrap goods. The paper, made by recycling rags, was sold back to the Franklins. The Franklins then sold the paper in the shop to Philadelphians and other North Americans as well as using it to print the news, books, and other small jobs. In the 1740s, the Franklins made over 1,500 pounds on the sale of paper alone.

Franklin’s encouragement of rag saving as well as his financial backing of papermakers supported his success in his print business and shop. In the twenty-first century, we can also see it as a community effort to produce needed goods through reusing and recycling materials. Overall, everyone in the community benefited. People who had rags would make extra money or gain credit in their account with the Franklins, Franklin was able to profit from the sale of the rags to the papermakers, the papermakers received the raw materials they needed to make paper, they were able to then sell it back to Franklin who then sold it to the people who sold the rags themselves.