The transactions in Franklin’s account books are a wealth of information about the daily lives of Philadelphians in the 1730s and 1740s. As seen with the interactive visualization below, one can discover what people were buying and selling from the unusual—telescopes and tar—to the most common—cash, advertisements, and books.

Account books in the eighteenth century look similar to accounting systems today in that they record detailed information about the purchase of goods and other transactions. However, there are a number of differences that affect the way the historic ledgers can and should be used. Eighteenth-century account books were not necessarily standardized, and the Franklin’s books were no excpetion. Although there were books and manuals, Franklin’s ledgers do not conform to them. This makes reading the documents difficult.

Use the StoryMaps below to orient yourself to the Franklin’s accounting system and the datasets created from them.

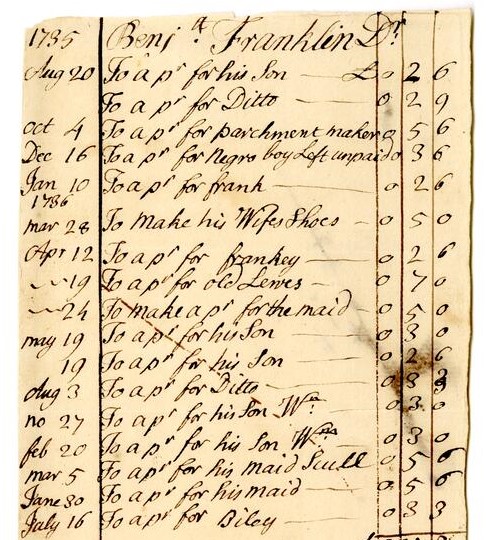

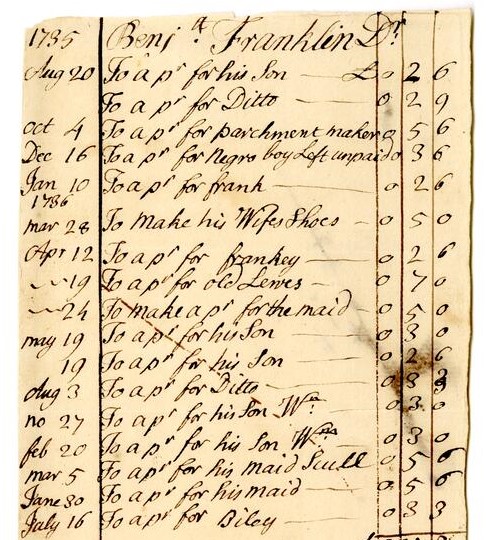

An account between Franklin and a shoemaker, including purchases of shoes for an enslaved person and Franklin’s servants.

An account between Franklin and a shoemaker, including purchases of shoes for an enslaved person and Franklin’s servants.

Slavery was a primary engine of economic growth in colonial America, and it is difficult, if not impossible, to disentangle colonial business from its reliance on forced and unfree labor. To participate in commerce was to benefit, at some level, from forced labor. The Franklins occupy an uneasy position in this economy: on the one hand, the Franklins enslaved at least seven people and regularly sold advertisements for enslaved people and fugitive slaves. On the other hand, the shop published and sold abolitionist texts by Benjamin Lay and Ralph Sandiford.

The Franklins’ ambivalence about slavery can also be understood through the ledgers. In spite of the Franklins’ business dealings with well-known abolitionists such as Lay, Sandiford, and Anthony Benezet, the economic system of British North America depended on forced labor and the Franklins’ business transactions profited from this system. They exchanged far more money with wealthy slaveholders, such as Reese Meredith, Nathan Levy, Robert Ellis, and William Crosthwaite. And products that relied on plantation slavery—sugar, rum, rice—were among the offerings of their shop.

To a lesser extent, the ledgers occasionally betray the presence of enslaved people in the Franklins’ business dealings. The Franklins occasionally record when an enslaved person conducted a transaction on behalf of their enslaver. We must additionally take seriously the possibility that the people the Franklins enslaved contributed to the running and management of the shop, even if this labor is not directly visible in the ledgers. This would have freed time for Deborah and Benjamin to do the administrative work recorded in the ledger and facilitated their economic rise. By providing these ledgers in a digital form, we hope researchers will be able to engage critically with the reliance on enslaved labor in eighteenth-century British North America.

Resources and Further Reading

Bradley, Patricia. Slavery, Propaganda, and the American Revolution. University Press of Mississippi: Jackson, 1999.

“Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade.”https://enslaved.org/.

“Freedom on the Move Project.” https://freedomonthemove.org/.

Keyes, Carl Robert. “The Adverts 250 Project: An Exploration of Advertising During the Era of the American Revolution, 250 Years Ago This Week."https://adverts250project.org/.

Nash, Gary. “Franklin and Slavery,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 150.4 (Dec 2006): 618-635.

“Penn & Slavery Project.” http://pennandslaveryproject.org/.

“SlaveVoyages.” https://www.slavevoyages.org/.

Smith, Billy G. and Richard Wojtowicz, Blacks Who Stole Themselves: Advertisements for Runaways in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728-1790. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989.

Taylor, Jordan E. “Enquire of the Printer: The Slave Trade and Early American Newspaper Advertising.” last modified June 21, 2020. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/7d6dcdc8d7a24d34a08f1605e64c292e.

Waldstreicher, David. Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.

Most of the entries in this volume were made by Deborah Franklin. Since these entries overlap with those in Ledger A, it is sensible to assume that the entries were made in whichever volume proved more convenient at the time, with Franklin more likely to use the Journal and his wife the Shop Book. Most entries appear under date of transaction. His printing ventures, goods sold over the counter in the shop and items for his business use or resale give an insight to the struggles to get ahead in the world, for he sold everything from ink and quills to printed legal forms and books.

This is the earliest known surviving Franklin account book. It was kept by Franklin and his wife, Deborah, and very few entries are in other hands. Paper was expensive and ruled books were especially dear: therefore, Franklin used the last half of this volume for Ledger B. Ledger A is the front half of the book and the entries are records of sales, purchases, printing expenses, bills, etc., under the date of the transaction, and then they were posted under the name of the customer in Ledger B. Only Ledger A has been transcribed.

This large (ca. 400 page) volume contains entries for credit sales but few payments, for legal forms, paper, ink, quills, etc., much like Ledgers A and B. Also, it contains records of dealings with many public officials of Philadelphia and the governors of Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey. In the 18th century, account books and ledgers were living documents, meaning that they were changed or annotated frequently to meet the user's need. To stay organized, the Franklins devised a multi-ledger system. Ledger D was the final stop for stop for customer transcations.