Deciphering Deborah Read Franklin’s World

In his autobiography Franklin wrote that his wife Deborah “assisted me cheerfully in my business, folding and stitching pamphlets, tending shop, purchasing old linen rags for the paper makers, etc. etc.” But little is known about Deborah Read Franklin’s life and world and even the most basic information about where and when she was born is contested. Her experiences as a young girl in Philadelphia are, unlike her husband’s childhood in Boston, basically undocumented. Even after her marriage to Benjamin, we only have a few descriptions written by her and her husband that reveal her experiences as a mother, wife, and contributor to the family businesses. Despite the relatively superficial documentation, we know that Benjamin entrusted her with his power of attorney when he was away and that she was crucial to the smooth running of the post office.

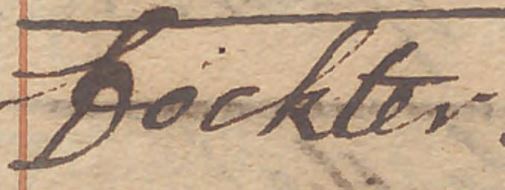

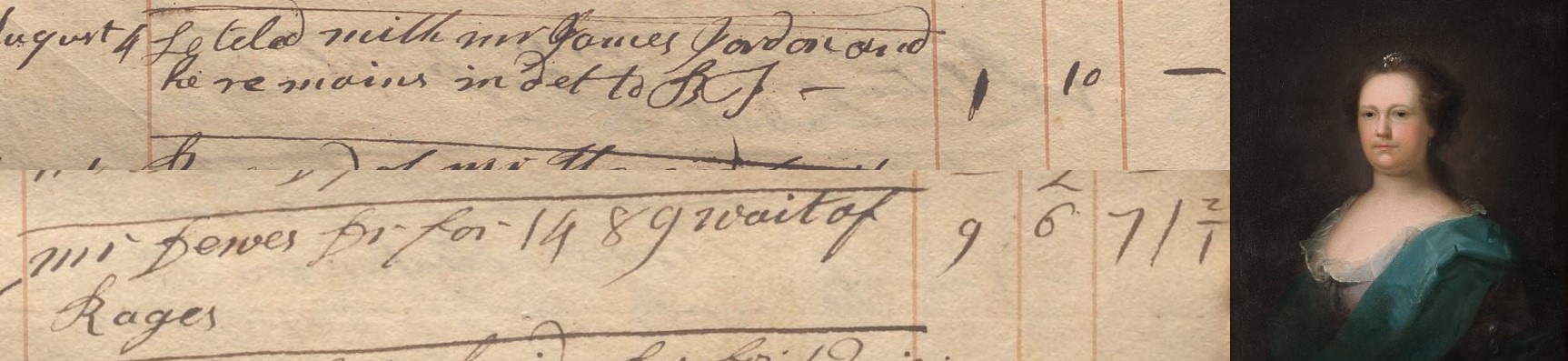

In recent years, scholars have reconstructed Deborah’s life and world through her letters as well as the Franklins’ account books. They are able to do this because Deborah had unique handwriting and spelling. Deborah’s education, most likely at home, was not like her husband’s. Benjamin was educated in a grammar school and was taught to write by George Brownell, who later lived in Philadelphia and purchased items in the Franklins’ shop. Additionally, Benjamin’s profession as a printer required that he hone his skills in spelling and standardization of punctuation and grammar. His time in his brother’s and other print shops also made him very conscientious of script and font. The educational differences between the husband and wife mean that their handwriting and spelling are distinguishable from each other.

Deciphering Hands in the Ledgers

- In the process of creating the dataset it wasn’t always clear whose hand we were transcribing so we needed to find certain distinctions. For example, we quickly learned that Deborah’s handwriting is more slanted than Benjamin’s and that he used more flourishes and embellishments in his writing. But during the transcription process, we found three main clues to deciphering the Franklins’ hands. Click below to learn more.

Visualizing the Shop's Activities

The variation in their handwriting provided the Franklin Ledgers Project with an opportunity to enhance the dataset by notating who entered the transaction in the ledgers. By compiling two account books—Ledger A and the Shop Book—with this additional information, the period in which the Franklins were building their business and how they divvied up the work can be more completely explored. Using network visualizations, it is clear that Deborah encountered a diverse set of Philadelphians and others, from preeminent individuals such as Thomas Penn, son of the founder of Pennsylvania and the Governor, to unknown individuals, bartering, completing sales, and preparing print orders. The network that Deborah formed through her work in the shop was almost as vast as Benjamin’s. She encountered over 660 people in the shop in the 1730s compared to Benjamin’s 837 individuals with only 275 of them being shared customers. As evinced in the visualization below, it is also clear that Deborah engaged in business with women more regularly than Benjamin. Out of over 2,500 transactions that Deborah entered in the ledgers in the 1730s, around 13 percent were for women compared to Franklin’s engagement with women, which was closer to 5 percent of his total transactions.

The following network visualization shows all transactions recorded in the Shop Book and Ledger A from 1730 to 1740. Each circle represents a person documented in the ledgers. By pressing “Play,” you can watch how the shop's business changed month by month. Clicking on a circle will open all of that person’s transactions in the Franklin Ledgers Database.

Back to top

- Top