The Journey to Indenture

In the years immediately preceding the American Revolution, over five thousand people entered into contracts of indenture at the Port of Philadelphia between 1771 and 1773. How did they travel to Philadelphia? And where did they come from?1

Most people arrived by ship, traveling across the Atlantic in search of a better life. Others came from within Philadelphia, voluntarily entering into indenture contracts or through coercion. The interactive map below plots the journey of over two-thousand individuals who found their way to America through the Port of Philadelphia.

Using the data to create maps helps us highlight patterns of movement. Visualizing the data in this way also highlights individual records that stand out as unusual. Find out more in the maps below.

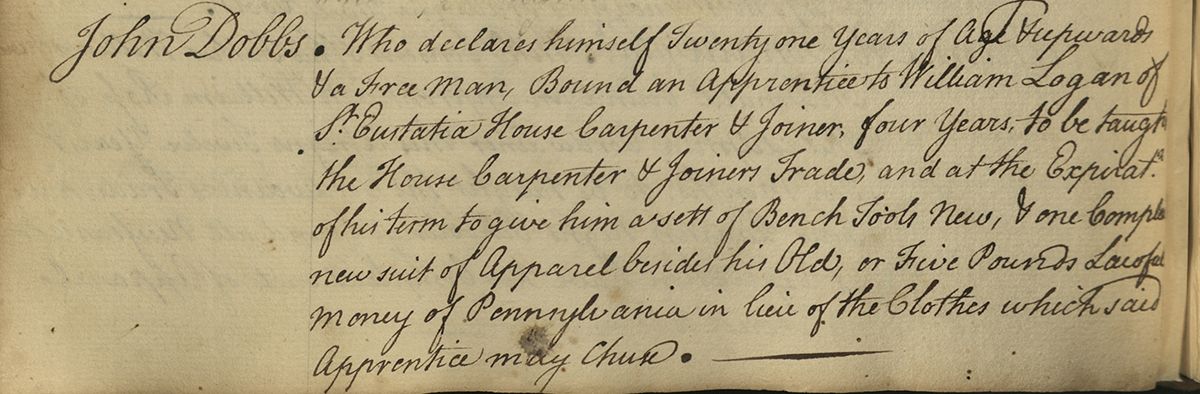

The Story of John Dobbs

When Dobbs' contract of indenture expired, he was to be given "a sett of bench tools new, and one compleat new suit of apparel besides his old, or five pounds laful money of Pa. in lieu of the clothes which said apprentice may choose." These "freedom dues" - tools, clothes or a sum of money - were a legal requirement, though many masters were known to ignore the law. The provisions were only paid upon completion of contracts and were an incentive for apprentices to complete the full term.4

Next Topic Gendered Indenture

- 1. Data note: We made several decisions when processing this data. First, we entered decimal latitude and longitude coordinates to the center of the smallest known geographical location (town, county, country). The maps depicting the movement of people to America is comprised only of records where we know the point of departure and location of bondage. This is approximately 2,000 records from a total of over 5,000. The sample on this map is not random and thus not necessarily representative of all bound migrants. It still provides a great deal of information not previously available.

- 2. This map of the island from 1790 details "St. Eustatia" to be a corruption of St. Eustatius.‘The Island of St. Eustatius Corruptly St. Eustatia - Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center’ Accessed 27 June 2019.

- 3. Enthoven, Victor. ‘“That Abominable Nest of Pirates”: St. Eustatius and the North Americans, 1680—1780’. Early American Studies 10, no. 2 (2012): 239–301. pg. 246

- 4. Grubb, Farley. ‘The Statutory Regulation of Colonial Servitude: An Incomplete-Contract Approach’. Explorations in Economic History 37 (1) (2000): 42–75. pg. 43